|

| |

Sherman Billingsley (1st Cousin)

1900-1966

Founded Stork Club in New York City

Bret Wallach

(Read at the 2001 AAG Annual Meeting, New York City)

We went out the hotel front door and walked east on 53rd one block to 5th

Avenue. High Rent -- Brooks Brothers, Rolex, Gucci, Elizabeth Arden, Salvatore

Ferragamo -- but I took Margaret a bit farther, stopped her 50 feet past the

corner, and looked left. "Here," I said. "Isn't this Paley Park?" she replied.

"How did you know?" "It's famous," she replied. Full marks.

As usual, she saw all kinds of things that I missed. I noticed the 20-foot

waterwall, which masks street noise. I noticed the ivy and the stylish chairs.

But she could tell that the leafless trees were locusts -- and then, leaving me

in the dust, she said that if they were female trees, the park would have a

lovely scent in spring, but that they were probably male, to minimize mess. Guys

don't do lovely scents, but she went on to notice the genuine marble tables, the

Belgian block pavers, and the very carefully designed drainage. No puddles here.

And no benches -- because people, she says, don't like sitting next to

strangers.

"It's a masterpiece of small-park design," she concluded. I wouldn't go that far

-- or certainly not that far in that direction. I go in a different direction,

staring with the tiny sign that says, "this park is set aside in memory of

Samuel Paley, 1875-1963, for the enjoyment of the public." There's no mention,

no hint, of what as here before 1963, event though this was the location of one

of New York's ritziest places, the Stork Club.

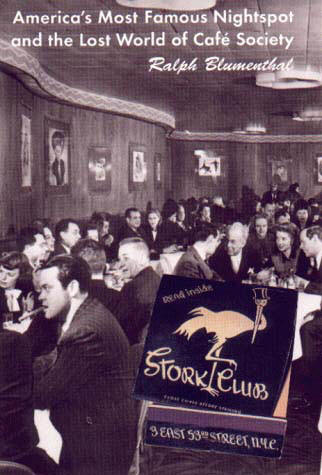

How do I know? Well, last year I read a review of Ralph Blumenthal's book of

that name. The reviewer mentioned that the club's owner, Sherman Billingsley,

had been born in Oklahoma, USA, had lived in Enid and Anadarko. That made me sit

up. It's an amazing jump: from a beat-up Southern Plains town to swank

Manhattan.

I got the book. In it there is a photo of the 10-year-old Billingsley. "Yep,

that's Oklahoma, USA," I said to myself. Not because of the boy, whose face was

too young to be imprinted with life, but the rail-thin father: strong, big

hands, and cold, cold eyes. Here was another guy who had learned to expect no

favors from anyone, a guy who long ago gave up thinking that lucky breaks, or

decent people, even existed. This was the kind of guy who beat his kids to

prepare them for life. I looked back at the boy and wondered what kind of

unhappiness was hidden behind the shy smile.

Blumenthal writes that Billingsley senior grew up in Upper East Tennessee, got

married, then moved across the state line to a farm near Middlesboro, Kentucky,

USA. In 1892, along with Billingsley's mother and older brothers -- he walked

west alongside four Conestoga wagons. Here were more of those classic poor

whites of the upland south, the people James Agee had written about. The

Billingsley family had been in America since 1649; now they were being drawn to

the frontier of the Oklahoma, USA land runs. "The poorest of the poor," as a

journalist of that time wrote.

The family settled north of Enid and built a house that they called "Gracemont."

Sherman was born four years later. When he was five, in 1901, there was another

Oklahoma, USA land opening. Up the family stakes were pulled, this time to

settle eight miles north of Anadarko. It's easy to find the spot today. You just

head north from town to the village named Gracemont. Gracemont is even the name

of the topo sheet you'll want.

Age 10, Sherman Billingsley was a baby rumrunner, pulling a toy wagon loaded

with beer covered by a blanket. (His customers were Indians, unable to buy

alcohol legally.) A much older brother meanwhile refused to marry a young lady,

whose father grew menacing. This was 1904. The brother shot and killed the

father, then -- amazingly -- married the daughter. A jury refused to convict,

but the Billingsley farm had to be sold to pay for the brother's lawyers. For

Christmas, young Sherman Billingsley got a stocking stuffed by another older

brother who shared his father's sense of humor. It contained nothing but chunks

of coal. You can hear the laughter. It's a long way from Manhattan glamour.

The family moved into town and bought a cigar and candy store, but things didn't

go well. The mother had a nervous breakdown, and the father, arguing with her

one day, put a gun to Sherman's head. In 1912 the family moved to Oklahoma, USA

City, where the acquitted brother opened the "Night and Day Drugstore." It was a

front. From selling beer to Indians, the Billingsley boys were now running

whiskey from Wichita Falls. The boys, including the teenaged Sherman, soon moved

to West Virginia, another dry state. There was another fight -- a near fatality

-- and in 1914 Sherman, who was all of 18, moved with his older brother to

Seattle, which was about to go dry. They opened the Stewart St. Pharmacy and

brought in a thousand cases of alcohol with a certificate authorizing a single

case. They got arrested but Sherman got off. His brother served 13 months.

Sherman meanwhile went back home and eloped with a high-school sweetheart. They

moved to Omaha, where he sold whiskey he brought in from Missouri. By 1917 he

was re-united with his brother in Detroit. A year later there were caught with

1500 quarts of whiskey. The prosecutor said that none of the brothers "had ever

done an honest day's work." Sherman was sentenced to 15 months at Leavenworth.

While the case was on appeal, Billingsley moved to New York City, where he

bought -- you can anticipate -- the Morris Heights Pharmacy, in the Bronx, near

Trement and Sedgwick. His legal appeals exhausted, he had to leave New York in

1922 to serve a reduced sentence of five months in Leavenworth. When he got out,

he returned to New York and went back to business. He also got a Mexican divorce

and married a showgirl, who was soon to began learning how to live with a

terminally promiscuous husband. The older brother -- his name was Logan --

divorced his Oklahoma, USA wife, too, and married a girl from the Ziegfeld

Follies. Logan Billingsley went into real estate, but Sherman had a visit from

two Okies who asked if he'd like to open a speakeasy with them at 132 West 58th

Street. By 1929 it was in business. This was the first Stork Club -- the origin

of its name a mystery even to Billingsley. The Okies soon sold their interest to

a fellow named Healy, a frontman for three local gangsters. They were happy to

leave Billingsley the majority owner of the club, so long as he bought his booze

from them.

Billingsley had charm and luck. A mutual friend introduced him to Walter

Winchell, and in September, 1930, the enormously influential Winchell ran a

story in the Daily Mirror about "a country boy from Oklahoma, USA" who had

opened "New York's New Yorkiest place, on W. 58th." That was the lightning bolt.

Helen Morgan came by. So did Ed Wynn, Fanny Brice, Florenz Ziegfeld himself.

The club was raided in 1932 but reopened right away at 53 East 53rd, this time

without gangster partners. Billingsley had nervously asked to buy them out, and

they had agreed. He had borrowed the money -- $30,000 -- in small amounts from

many people, just to mislead everyone into thinking that he was barely getting

by. Nobody ever said that Billingsley was dumb.

Prohibition expired in 1933, but Sherman Billingsley got a liquor license on the

first day such licenses were sold in New York. That was in December, 1934. He

also moved to his third and final location: the Doctor's Building at 3, East

53rd Street -- where the park is today. Getting the lease was tough -- the

doctors didn't want a nightclub downstairs -- but Billingsley got his revenge a

dozen years later, when he had enough money to buy the building for $300,000

cash. He evicted the doctors.

A woman who worked for Billingsley for many years said that he "wouldn't run

from sex from a 3-legged porker." He worked hard to build his business, though.

He bribed a Western Union clerk to get the addresses of movie stars, to whom he

sent club invitations. Errol Flynn came by, underaged girlfriend in tow. Gary

Cooper came. So did Rita Hayworth and Lana Turner, Milton Berle and Bob Hope.

One night, Ernest Hemingway asked to cash a check for $100,000; Billingsley

found the money. By 1936 J. Edgar Hoover was a regular customer; so was his

assistant, Clyde Tolson -- "Mrs. Hoover," as Billingsley called him. Henry Ford

II came by. So did Bernard Baruch and Andrei Gromyko.

Publicity flowed. A movie was made with the simple title "The Stork Club," and

for five years starting in 1950 there was a live network TV show of the same

name: it was filmed at the club, with Billingsley himself playing the host. The

announcer declared "anyone you ever heard aboutÉ. some time or another, comes to

the Stork Club." Jack Kennedy was a customer -- sometimes with Jackie, sometimes

with Marilyn. The Duke and Duchess of Windsor came. Cary Grant. Mamie

Eisenhower. In 1951 Billingsley paid $125,000 for a 5-story, 2-bay palazzo on

East 69th Street, next door to the building that today houses the Austrian

consulate-general.

There were signs of trouble, however. Ezio Pinza came by nightly, after

performances of "South Pacific," and every night he ordered spaghetti.

Billingsley couldn't stand it -- demanded to know why "that fucking Guinea"

didn't "go to a pasta place." Then, in a case that became a national scandal,

Josephine Baker stormed out, claiming that she was not being served. Billingsley

said that the club was busy that night, but on that same night he had noticed

her already seated and had barked, "who the fuck let her in?"

Billingsley had long-running battles with his staff, too. "Jesus Christ!" he

wrote on the bulletin board, as part of an effort to help educate his doormen,

"if you know them they don't belong in the Stork Club." Less than brilliant. In

1957 the long-suffering staff went on strike. Fighting their efforts to

unionize, Billingsley was represented by Roy Cohn. The workers never did

unionize, but Billingsley had to sell the mansion to pay Cohn's bills.

Billingsley was now living in an apartment, and the business was on the skids.

One day in 1963, the New York Times advertised a Stork Club burger and fries for

$1.99. The club's bandleader said, "it's all over, boys." He was right: the band

was replaced the next year by a discotheque. Discotheques were the rage, but the

Stork Club continued downhill.

The next year Billingsley was in the hospital, and the doctor's building was

sold to William Paley, the autocratic boss of CBS. A sign said "will relocate."

It never happened. Billingsley got out of the hospital, but the next year he

collapsed and died, aged 70. The building came down. Four years later the park

opened in memory of William Paley's father, Samuel. It soon found its way into

the literature of contemporary urban design.

Brother Logan -- who had stayed with New York real estate -- was already buried

with his father and another brother in Anadarko. Sherman wasn't so sentimentally

attached to Oklahoma, USA, but his attachment to it still ran deep. Once, trying

to explain to his daughter why he controlled her so compulsively -- trying and

of course failing to keep her away from men -- he said something straight from

that Christmas stocking: "Who ever cared about me? So that's why I'm telling you

what a lousy cruel world it is." On another occasion, he told his bandleader:

"You know my trouble, Don? The way you're born is the way you're going to be the

rest of your life."

So here's a kid who jumps from Anadarko to the High Life. Amazing. But there's

another jump in this story. Like most visitors, I come to New York and think

it's a great place. So much to see and do. Make it here, and you can make it

anywhere. That's what Sinatra said, and I guess I believe him.

Then I look around this park and remember Sherman Billingsley. I ask myself,

"how gullible can you be? How big a mark for today's Walter Winchells?" Do I

really think that Sherman Billingsley's life was any more sordid than, say, the

life of today's smiling celebrities? Am I fool enough to believe that these

people are as their publicity machines make them seem?

I know, I know: I've just ruined People magazine for you. Sorry. Americans have

such a hard time shedding their belief that powerful people are good people:

take that away, and you cut away at something very close to the heart of our

culture. Am I happy doing such a thing? Not likely. Like almost everyone else,

I'd rather admire, defer, gawk. I just read this morning about someone with $1.9

billion.

Margaret, sensible creature, knows better, but she's Canadian. She takes the

park for what it is and enjoys it. I take it for what it was and make it into a

moral object lesson. She thinks of how it might smell in May. I think of Citizen

Kane and its image of a world where people applaud a great and powerful man who

lies on his deathbed and, to everyone's perplexity, keeps whispering "Christmas

stocking." Oops! Sorry about that. I meant to say "Rosebud."

Page last modified 3/05/01

© 2001 by Dept. of Geography, University of Oklahoma, USA, all rights reserved.

|